Broadway Profiles – A Serial Interview with Jack Viertel Part Three

May 2, 2019

Content has been edited for brevity and clarity

PART THREE

I’m curious to hear your thoughts on this, as you’ve had experience as both a commercial producer and a theater critic. I’ve noticed that more and more, the reviews are not always in line with popular opinion and have heard that the world of theater criticism is shrinking. Why do you think that is?

I think there are a few answers to that. Probably the most important reason that theater criticism isn’t as powerful as it once was isn’t that the theater critics are less good – which is a debatable point that one could have any number of opinions about – but that the audience is now so broad and from so many different places that they’re not buying tickets based on reviews anymore. Someone planning a trip from across the country – or the world – decides what shows to see based on various kinds of marketing, including social media and advertising, and they don’t really know whether the critics liked the show.

When I was young, back in the early 60s, the audience was still largely based in New York and its suburbs. Everyone read the reviews and cared about what the critics said because there was no alternative information. There was no social media or ads on television, for example; the critics were kind of it. Even the advertising that was done marketed the show through quotes from the critics. They were the only real taste-makers. Now, theater criticism has to compete with an ever-broadening audience and an ever-broadening way of distributing information. It remains powerful for certain kinds of theater where there’s still a New York-centric audience, but that’s no longer the lion’s share of theater-goers on Broadway, so Broadway primarily produces for international and national audiences. And this isn’t just an issue for theater criticism, of course, it’s a problem for journalism everywhere. Newspapers are disappearing – my old alma mater, the Herald Examiner, hasn’t been around for a long time. We don’t expect the paper to hit the driveway in the morning — we turn on our phones and can check out a half-dozen news sources on the same screen at the same time.

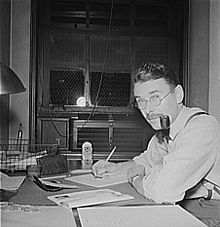

I think as a result, many theater critics feel empowered to write in a way that is less about reporting what they saw on stage last night (and having an opinion about what was good and what was bad about that) than it is about trying to push the art form in one direction or another depending on their own aesthetics. I’m not saying that’s an invalid thing to do, but it’s different than what Walter Kerr and Brooks Atkinson were doing, which was essentially a reporting job with opinion added. There isn’t as much reporting in today’s theater criticism, but there’s a lot of opinion. A lot of the opinion is about the show but just as much is also often about what the production represents in terms of where the theater is going. I think that becomes a slightly inside baseball argument among people who want to talk about the aesthetics of an art form and much less a general interest piece of writing about whether to attend a show. It seems that many critics have taken on the responsibility of helping establish where the art form goes.

And of course, politics have always been relevant in theater and art, but it seems that we are seeing an extreme increase in the infiltration of politics both in productions and within theater criticism.

Yes. It’s geopolitics, but it’s also sexual politics and racial politics and I think it works in both directions. Critics can be, to me, overly critical of shows that are not involved in politics or revivals of older shows whose sexual or racial politics feel outdated, but they can also give a pass to some shows that are not particularly well done but are passionately making a contemporary point. Now, this is only my opinion and not necessarily the next person’s opinion, but that’s what I sense; many critics are driven toward or away from certain pieces based on things other than “I had a good time” or “I didn’t have a good time.”

Would you say that this evolution of theater criticism is having an impact on the industry and the kind of work that is being produced?

I think it may be having an impact on the non-profit part of the industry more than the commercial. In my opinion, the commercial part of the industry is heat seeking toward an audience and they’re not worrying too much about the critics. When you look at the evidence of shows like Wicked, which was not well-reviewed for the most part and has run for decades anyway, (or shows that got wonderful reviews and didn’t run because there was no real commercial audience for them) I think most Broadway producers view critics as an adjunctive entity that comes with opening a show. The critics are smart, so it’s nice to get good reviews, but from a marketing point of view, it’s less essential than it once was.

You have extensive experience in both the non-profit and commercial world. Is there any overlap between the two, or have they become polar opposite worlds?

I think they’ve become partners in a way. It’s like a Venn Diagram; there is a big chunk of work in which only non-profit or commercial producers would be interested, but there’s a certain amount in which both would be interested. In that overlapping portion, the worlds can work together. For example, many commercial producers will give enhancements to non-profit theaters to try out their shows. The non-profit and commercial producers can talk to each other about where the theater’s going, where it’s been, what’s good, and what’s bad. But each also has their own work that they’re doing for their own mission and interests.

I’m changing topics a bit here. When looking through your bio, I noticed that you credit yourself as both a dramaturg and a creative consultant. Is there a difference between them?

There is in the sense that as a creative consultant, you might be called upon to help a producer refine a list of directors or composers, for example, to hire for a project. I don’t consider that dramaturgy. But once a project is started, I think creative consultant is just an American way of saying dramaturg. So, I don’t particularly distinguish between them once that process has begun.

Would you say that dramaturgs are more prevalent in the non-profit arena than the commercial? I rarely see a dramaturg credit in a Broadway playbill.

Yes, and also in European theater (which is largely non-profit). In these worlds, it’s actually a defined job, rather than just associate to the producer. Dramaturgs do research for the cast and director and write program notes; they’re involved in the semi-academic side of surrounding the production with knowledge. They aren’t necessarily tasked with helping a production creatively or working on the script, as a lot of the shows are classics, but they provide research and facts which help the audience appreciate whatever they’re seeing. In commercial theater, I think, we use the term more to mean someone who’s working to help the creators make a better show.